Welcome to my blog! Being a daughter of a hard working farmer I know that the only way to cure hunger is to grow food. I chose to do my college English research paper on farming and it impact it has one hunger locally and around the world. The following are the fruits of my labor. I hope by the end of this blog you will understand what I now do, that small local farming is the key to curing hunger in every part of the world.

Christina Todd

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

Edible School Gardens

Christina Todd

ENG 102

Final Local Research Essay

March 8, 2011

Edible School Gardens

Their Role in the Fight Against Hunger and Creating Volunteers of the Future

This report looks at both the pros and cons of implementing ediable gardens into all public and private high schools and jr. high schools in Boise to help relieve the ever growing burden to feed the hungry in Idaho. Using the obesity epidemic, the lack of knowledge of how to care for yourself if you find your plate bare, and the slow decline of volunteering as all strong arguments for the garden plan this reports details my belief that the future is held in the ways of the past, when your only option of survival was to work land and produce a crop.

Christina Todd

ENG 102

Final Local Research Essay

March 8, 2011

Edible School Gardens – Their Role in the Fight Against Hunger and Creating Volunteers of the Future

It is just before 10am in Wendell, Idaho, a small farming town of 2,430 people, when David Proctor, Public Affairs and Media Coordinator for The Idaho Foodbank, and his co-workers arrive at the Wendell Firehouse with the Mobile Pantry. The Mobile Pantry is a program run by The Idaho Foodbank that delivers food to rural areas of Idaho that does not have the facilities set up to store the food that the Idaho Foodbank delivers. Working together with local volunteers the Mobile Pantry is responsible for delivering 2,585,079 pounds of food every month to the many high poverty and remote areas in the state (IFB 11). David is greeted by the many volunteers from the Fire Department and the local church and together they unload the donated food onto five large fold out tables lined up in front of the firehouse doors. Already a large line has formed; David has learned they have been there for almost four hours, hoping to get enough food to feed their family until the Mobile Pantry returns in a month. “It didn’t just resemble a depression era soup line,” states David, “it was one.” This is an all too common scene in Idaho; skyrocketing gas prices and food cost have left many families wondering if they should pay the rent/mortgage, pay for gas, pay for utilities, or pay for food (PROCTOR). In 2006, 2008 and 2010 faith leaders, charitable emergency food providers, state and local government, health providers, advocacy groups, business and industry, and community leaders in Idaho met for the Summit on Hunger and Food Insecurity to try and discover ways to end Idaho’s hunger problem for good. While many great ideas where addressed in these summits such as raising the minimum wage, repealing the sales tax on food (ISH 2006 5), universal school lunch for all children, changing the asset test for food stamp eligibility (ISH 2008 2), developing an Idaho Food Stamp outreach plan, and increasing participation in the Summer Meal program (ISH 2010) no one was discussing where to get the food from or how to help relieve some of the pressures of finding food from the shoulders of organizations like The Idaho Foodbank. Maybe being a daughter of a farmer has made me more aware of what the land can produce, but I feel Idaho is ignoring a great resource for fresh vegetables and fruit by not looking at the relationship between schools and local food pantries and how using mandatory involvement and by the students to grow, cook and process food for the hungry will not only impact hunger but also impact volunteerism for years to come.

The Idaho Foodbank is one of only 200 organizations like it around the entire United States. Their sole job is to find and distribute food to the over 200 food pantries located throughout Idaho. This is a very hefty job as Idaho was ranked 13th in the nation by The Food Research and Action Center for food hardships in the first half of 2010 (FRAC). The Idaho Foodbank is run like any other distributorship; they receive and store product in large warehouses located in Lewiston, Pocatello, and Boise everyday they work to fill the never ending orders given to them by local food pantries, churches, schools, and even whole rural towns, like Wendell. Unlike their profit counter parts though The Idaho Foodbank runs solely off donated and purchased food and money from Idaho’s citizens and businesses. Scenes like the soup line described by David Proctor is a sadly a common scene in Idaho as of late, one only has to look at the jump in statistical numbers to see that the state is in need of some relief and fast . In 2010 the Idaho Foodbank distributed 8.9 million pounds of food or 6.98 million meals, up from 2009 when 6.8 million pounds or 5.3 million meals were distributed (Proctor). In 2010 The Idaho Foodbank along with their partner Feeding America surveyed those receiving food help and discovered that:

· 47% of those receiving emergency food assistance in Idaho reported having to chose between paying for food and paying for utilities or heating fuel

· 34% had to choose between paying for food and paying for their rent or mortgage

· 34% had to choose between paying for food and paying for medicine or medical care

· 37% had to choose between paying for food and paying for transportation

· 49% had to choose between paying for food and paying for gas for their car

As previously stated, the Idaho Foodbank is Idaho’s leading solider in the fight against hunger. “71% of partner food pantries rely on The Idaho Foodbank as their single most important source of food” (IFB 4). They have many successful programs, like the Mobile Pantry, geared towards helping families in need. They are a part of The Grocery Alliance Program, which is a program that works with local grocery stores to collect close date fresh fruits and vegetables, dairy products, grain and protein and deliver them to the Idaho Foodbank storage unit. “It is important to note that just cause a product says sell by does not mean it has gone bad. Every day a staff member of the Foodbank picks up close dated food from stores like Fred Meyer, this is our number one source in delivering high-quality fresh nutritious food” (PROCTOR). Indeed it is, in 2010 the Grocery Alliance Program helped deliver 2,035,185 pounds of food to the Idaho Foodbank, up a hefty 141% from 2009 when they helped deliver 843,592 pounds of food (IFB 8). In 2009 The Idaho Foodbank was proud to introduce the Beef Counts, Idaho’s Beef Industry United Against Hunger, the first ever program of its kind in the United States. Ranchers, action yards, feedlots and industry associations work together to provided beef to Idaho’s families (IBF 10). Another program, one dear to David Proctor’s heart, is The Backpack Program. This program was devised many years ago in the mid-west when an elementary school teacher noticed kids, who relied on the school system’s cafeteria for food, where coming back from their weekend hungry. Schools along with their local food pantries began sending home small bundles of food to get them through the weekend. It was soon discovered that many kids were not taking advantage of this program because they were embarrassed to be seen by their school friends taking home food. Introduce the backpack, now at the beginning of every school year teachers and school administrators get together to determine who is in the most need of assistance; those children are given backpack full of nutritious and easy to prepare food every Friday. Each sack cost $6.11 to prepare and contains two breakfast, two lunches, two dinners and two snacks, enough food to make sure all students return on Monday well nourished. “The sad fact is right now we make 2000 of these. Every week we set up an assembly line on these tables,” David points to a long line of tables arranged along the back isle of the Boise warehouse, “where we stuff bags to be delivered to the schools knowing that we could easy fill 7000 backpacks if we had the ability too” (PROCTOR). 5000 kids in Boise go hungry every weekend, does that seem right? Should we be letting this happen? Can we stop it from happening?

The truth is hunger may never end, there are too many variables one must control, like the economy, to ensure everyone prospers, never in a time of history has the entire world been free of hunger, but are we really doing all we can? The answer is no, the state is overlooking a very important tool, the schools and their students. Schools should not only be used as tools of education, but also factory work shops producing things to help the community that supports them with a free education. In the case of hunger relief the blueprint is simple; there are 16 public and private high schools in Boise city limits (BOISE). Imagine if working together through their graduation required elective classes’ students at each school grew and maintained a minimum 30’ x 30’ edible garden for local pantries. At harvest time, which Boise is fortunate enough to have three, students would deliver half their bounty to the local pantries on a daily basis and half would be sent to the schools home economics class room where more students would learn to cook, jar, and preserve the fruits and vegetables, their creations would also be delivered to the local pantries. This would ensure that at least 5 months out of the year a strong influx of food support would be coming in from various schools and thus helping to relieve Idaho Foodbank’s struggle to find enough food to feed those in need. “We have taken a big hit this last year in our food supply from the big chain stores, like Wal-Mart, have opted to sell their damaged and mislabeled good to the dollar stores instead of donating it to us and taking the tax write off. We need all the help we can get,” says David Proctor. The benefits of edible school yards reach much farther than just helping those in need they also offer students the knowledge of healthy eating, give them the skills to grow, cook and preserve their own foods, and teach them the value of volunteering.

16% of America’s children are obese. Over the last 30 years the number of children ages 12 to 19 who are obese has tripled, it can officially be called an epidemic. According to an article published by the Nutrition Journal “Overweight and obesity in childhood are known to have significant impact on both physical and psychological health” Cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary diseases, and gastrointestinal problems are just some of the things obese children have to look forward to in their future since studies state that 80% of overweight kids will grow up to be overweight adults (DEHGHAN). The school garden plays a very important role in teaching America’s youth about the importance of eating right. Erin Oxen, MS, RD and Amber D. King, MS, RD published an article through the School Nutrition Association looking at the direct link between school gardens and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption. Their report looks at the edible garden’s impact on children’s food choices. They believe that many children do not have the opportunity to encounter fresh fruits and vegetables. If children are allowed to discover them because of a school based learning garden programs they will not only know how to make and eat healthy foods but want too (OXENHAM). School gardens also touch another side of the of the obesity epidemic , the decline of physical activity in today’s youth brought on by TV, video games, and busy parents (DEHGHAN). Many researchers believe gardening can be a great alternative to a traditional 30 minute work out. Working in the garden helps strengthen your endurance, resistance, flexibility, and strength. Digging, spading, and transplanting dirt and soil works the upper body, back and legs. Weeding, planting and harvesting work hands, forearms, shoulders, legs, hips and hamstrings (RINDELS). Any activity that can get America’s kids to eat better and move more is essential to fighting the obesity epidemic, taking an hour out of a child’s school day for garden activity is giving them the tools to be healthier adults.

There was a time in America’s not so distant past that the majority of families living in America lived off what their land produced and what wild game that could be shot, hooked, or trapped. If you didn’t posses the skills to grow a garden, preserve the bounty and cook from scratch, you would starve by mid winter. When did it become okay not to teach our children how to survive? In the winter of 2006 Stephanie Bella found herself and her family faced with some of the same questions that the Idaho Foodbank was asking its families. How are we going pay mortgage and eat? Should I pay for gas or get food for our three year old? What are we going to do about the power bill, if we pay that how are we going to get food? “I was having a real bad day after making another call to another utility company begging for more time,” Stephanie recalled, “ I was crying at our patio door when it dawned on me, I own land, I know how to work land, I know how to grow things and preserve things.” Stephanie was born on a family farm in California which produced enough crops to feed her family, her uncle’s family, and her grandparents. Besides the main money producing crop of apples, the ranch was lined with blackberry bushes and strawberry plants, which every year when ripe Stephanie, her sister, and her two cousins picked and brought back to their grandma. Under their grandma’s supervision the girls were taught to turn the berries into jams, pies, frozen treats, and what was left over was frozen to be used later on that winter. The same was for said for the vegetable garden, the herb garden, the two avocado trees, the four orange trees, the plum tree, and the two lemon trees – breads and muffins were baked, fruit preserved, salsa made and jarred, spices made and vegetables stored. For the past four years Stephanie has produced a large kitchen garden in her backyard, she grows vegetables in a 15’ x35’ space along her house, container herb gardens grow in all her windowsills, she has an apple tree and plum tree and her fence is lined in berry bushes and grapes. “Don’t get me wrong, we still struggle, especially in early spring when the harvest runs out and the new one has yet to be produced, but my grocery bill certainly feels the relief of harvest time” (BELLA). She welcomed a new addition to her family this past June and has yet to purchase a single store bought baby food container, “I pureed tons of vegetables and fruit from out garden last year and froze them, and that is what Charlie has been eating since he started on solid foods (BELLA). Stephanie was given the skills to help care for her family in times of crisis; all kids should be given that same opportunity. Edible school gardens have the potential to teach children how to never go hungry, to rely on themselves first and not on agencies like The Idaho Foodbank and their partners, lack of knowledge in these areas have lead people to look more for a handout then to do the dirty work themselves, this way of thinking will not prove victorious in the fight against hunger.

Edible school gardens have the ability to produce volunteers of the future. For the past ten years government and school districts have worked together to try and establish mandatory community service for graduation (CQ). This requirement will prove very important in establishing the edible school garden plan. Summertime is the busiest time in any gardens life, unfortunately that is also the time that school and its projects are the furthest from any child’s mind. Studies have shown that participating in some form of community service, be it voluntary or not, positively influence adult volunteering. Forcing children to become involved in issues like their community’s hunger problems puts them directly involved with personal situations instead of just reading about them, if they are able to put a face to hunger, things like having to give a week of their summer vacation will not seem like such a sacrifice. Over an eight year period Daniel Hart, Thomas Donnelly, James Youniss, and Robert Atkins studied the relationship between high school community service and community service as an adult. Their finding indicated that “both voluntary and school required community service in high school were strong predicators of adult voting and volunteering” (HART). The United States has seen a dramatic decline over the last five decades of those willing to give up their own personal time to help those less fortunate as them, by introducing the school gardens to this generation, if Hart and his associate’s findings are true; we will be building a foundation of volunteers for years to come (HART).

There are barriers and challenges to implementing gardens into schools. Some are quick fixes like those who are concerned about the lack of curriculum associated with a garden based class. When it comes to implementing a school garden curriculum California gets an A. Universities all over the state have researched and developed study guides and training sessions for teachers and schools (TAFT). Other barriers are not quite so easy to conquer like funding, the over abundance of vegetables and fruit that people don’t know what to do with and essential let go bad, and people’s beliefs that children should not be forced to do any sort of community service for any cause.

Funding is the largest of these road blocks, but all good plans need capital to get off the ground and the edible school yard plan is no different. In a state whom finds themselves in the middle of a brewing war over education reform, the last thing Idaho thinks it needs is an experimental project that cost more money. According to Alice Walters, founder of the Ches Panisse Foundation, the annual budget for The Edible Schoolyard in Berkeley, California is $400,000. However, the Edible Schoolyard needs to be looked at as the top to the mountain and not, by any means a starting point. The Edible Schoolyard is a one acre piece of land next to the playground at Martin Luther King Jr Middle School that Waters along with sixth, seventh and eighth grade students transformed into an edible garden in 1995. Ten years later it is a thriving kitchen and garden class room geared toward food prepared by the students for the students (ORENSTEIN). To scale it down and bring it closer to home, meet the Northside Elementary School Garden Club, an after school program developed by Gail Burkett, Janet Clar, Sharon Burdick, Jill Edmundson, and Michele Murphee in Northern Idaho. Murphee says they did not know what to aspect on their first meeting and were surprised when thirty-three kids signed up for an hour after school every Monday. The club received a grant from the Community Assistance League to buy equipment like shovels, gloves, clippers, seeds, and a wheel barrow. People and businesses also pitched in donating plants, soil, manure, and compost bins. Murphee and the other women were surprised by how hard the kids were willing to work, “they shovelled dirt and manure, built beds, and planted like crazy without complaint” (MURPHEE). At the end of their harvest 100 pounds of lettuce had been produced as well as carrots, peas, green bean, squash, tomatoes, potatoes, berries, onions, peppers and pumpkins. The children’s bounty was sent off to the local food pantry. All in the entire entire project cost about $3000.00, and a lot of hard work by students, parents, and faculty (MURPHEE). When and if a project like this where to every get pitched to the Idaho School Board a $3000.00 a year price tag is better sounding then $400,000.00 one.

People’s lack of knowledge of how to prepare fresh vegetables is a major problem for the Idaho Foodbank. David Procter tells me that every year when donated garden vegetables are handed out people look at them and say, “What am I supposed to do with this?” The problem has gotten so bad that not only is food handed out, but recipes on how to prepare it as well, still the stares continue. “This is a big problem. Every year we know a lot of pounds of food is wasted because people don’t know how to prepare it,” David says. Take zucchini for example, The Idaho Foodbank’s number one donated garden produced vegetable, anyone taught about vegetables and how to prepare them would know that zucchini can be chopped up to replace half the hamburger need in any recipe or that it can be thinly sliced and mixed with spaghetti noodles thus extending your food longer, you don’t use as much hamburger and you don’t use as much noodles. If you don’t have the skills of course you would look at a raw vegetable and question how this will help you. If the garden plan were implemented future generations would know what to do if handed a basket of fresh vegetables instead of looking at it as if it were some sort of foreign object.

Forcing students to tend a garden and cook for the poor walks a fine line between citizenship and slave labour, bringing back the debate started in the first President Bush’s time in office, should schools be allowed to force mandatory community service for graduation? Over the past ten years the number of high schools requiring mandatory community service has steadily increased with students being required to complete anywhere from 40 to 100 hours before they can graduate. Most people would agree that community service is a good thing; however the group is quickly divided then the word mandatory is included in that statement. Some have gone as far as to sue school districts for violating the constitutional prohibition of slavery. Opponents of mandatory community service argue that students “are already overwhelmed with homework, exams and college applications,” (SASLOW) and should not be forced to take on yet another task unless they chose of their own free will to do so. What right does the government have to tell people that they need to help feed the poor and hungry? Of the many opponents I ask is this really a government issue or a human rights issue, isn’t every human afforded the right to eat?

There is no solution to hunger; only armed with hard work, knowledge, and innovative thinking can we even begin to make a dent in it. The edible school yard can provide the adults of tomorrow with the skills to better serve their community, to help their families in times of need, and help them be healthy and well nourished human beings. This could also just be the beginning, imagine implementing jail edible yards, and community run farms all working under the same umbrella of hard work and knowledge to end hunger. “We all have contributions to make in ending hunger and malnutrition and that each one of us, even in small ways, can be a hero to someone else” (FEEDING). I encourage everyone to plant a garden this spring and see where it takes you.

Works Sited

BELLA: Bella, Stephanie. Personal interview. 26 Feb. 2011

BEJAR: Bejar, David. Mendoza, Rosa. Rizal, Rachel. Shetty,Keerthi. “Children’s Diets & the

Benefits of School Gardens a Report for the Princeton School Gardens Cooperative.” Tuft Scope University 8.2 (2009): 36-41. Print

BOISE: Boise District Schools “Find a School”. Independent School District of Boise City.

Web.

CQ: “The New Volunteerism,” The CQ Researcher. 13 Dec (1996): 6.46. Pages 1081-1044.

Print.

DEHGHAN: Dehghan, Mashid. Akhtar-Danesh, Noori. Merchant, Anwar. “Childhood obesity,

prevalence and prevention.” Nutrition Journal 3.33 (2005). Print.

IFB: The Idaho Foodbank 2010 Annual Report. “Leading the Effort to End Hunger in Idaho.”

Boise: Idaho, 2010. Print.

HART: Hart, Daniel. Donnelly, Thomas. Youniss, James. Atkins, Robert. “High School

Community Service: as a Predictor of Adult Voting and Volunteering.” American Educational Research Journal. Vol 44. (2007): 107-219. Print.

ISH 2006: Idaho Summit on Hunger and Food Insecurity. “Making a Place at the Table for All

Idahoans”. Final Report Summit Conf. Boise: Idaho. 27 Oct. 2006. Print.

ISH 2008: Idaho Summit on Hunger and Food Insecurity. “Healthy Decisions for All”

Idahoans”. Final Report Summit Conf. Boise: Idaho. 10 Oct. 2008. Print.

ISH 2010: Idaho Summit on Hunger and Food Insecurity

Stopping Hunger Before it Begins. Final Report Summit Conf. Boise: Idaho. 19 Oct. 2010. Print.

FRAC: Food Research and Action Center Food Hardship: A Closer Look at Hunger State Data

through June 2010. Dec 2010. Web.

MURPHEE: Michele, Murphree. “Edible Schoolyards Sprout in North Idaho.” Northwest Food

News. 1 Jan. 2011

ORENSTEIN: Orenstein, Peggy. “Food Fighter.” The New York Times 7 March 2004. Print.

PROCTOR: Proctor, David. Personal interview. 15 Feb. 2011.

SASLOW: Saslow, Linda. “High Schools Mandating Community Service.” The New York

Times 1 May 1994.

REINDELS: Reindels, Sherry. “Gardening for Exercise.” Iowa State University of Science and

Technology. 10 Nov. (1993): 161-162. Print.

Jack, Jessica and Me. Our adventures in Vegetable Deception.

Jack, Jessica and Me. Our adventures in Vegetable Deception.

|

| Jack showing what he thinks of veggies. |

Recently I have run into a road block with my 20 month old son Jack, he absolutely refuses to eat vegetables. When he first made the leap from baby food to real food he was eating vegetables like they were going out of style. I spent six months bragging to everyone how my kid would eat any vegetable I put in front of his face, now that is no longer the case. His hatred of vegetables has gotten so bad that when I make spaghetti sauce with fine chopped onions, zucchini, mushrooms, red peppers, and green peppers he will take a bite and then slowly and diligently work the veggies out of his mouth before swallowing the pasta. This will not work for me first I love vegetables and every meal I eat contains at least two and second I think one of the most important things I can pass on to my kids to good nutrition, but this strike is starting us off on the seriously wrong foot.

Enter in my savior Jessica Seinfeld, wife of Jerry Seinfeld, mother of three and professional vegetable hider. In her cookbook, Deceptively Delicious, Jessica introduces the art of pureeing vegetables and putting them into foods that all children will love; just what my anti veggie son needed a little trickery. Following in the same idea employed by Julie Powell when she cooked her way through Julia Child’s cookbook Jack and I are going to cook our way through Jessica’s book. We won’t have the same quick witted flair that Julie possessed, but we will fight through this book, at least until he is old enough to comprehend the phrase “you aren’t leaving this table until all those vegetables are done mister.”

Adventure One: Blueberry Muffins with Yellow Squash

I chose this recipe fist since muffins are basically cake for breakfast and what better way to start the deception then with cake. Because I am a mom, a full time worker, and a student I bypassed on making everything from scratch as the recipe suggest, I bought some whole wheat blueberry mix in a box. Jessica is married to a rich guy and doesn’t have to work; I don’t have time to be baking from scratch. Jessica’s recipe called for ½ of cup of yellow squash puree, I decided to triple it, veggie intake is the goal here, as the old saying goes, go big or go home. In this family we go big. The first thing I noticed was it takes a lot of puree yellow squash to make a cup and a half, four whole ones. I felt bad when the dried blueberries came out of the box so I also added another cup of frozen ones. For those on a budget, like my little family is, it was a nice surprise that with all the additions to the ingredients we added 6 more muffins then the box said it would make. These were an instant hit, not only with Jack, but with the anti-veggie eating husband as well. 4 yellow squashes in 18 muffins, not bad for breakfast, though I still maintain muffins are just cake with our frosting.

Adventure Two: Grilled Cheese Sandwich with Butternut Squash or Sweet Potato

It took my three times to get this recipe right and unlike the muffins I had to end up following the recipe to the letter. The first time I tried this one I did a ½ cup of butternut squash puree and a ½ a cup of sweet potato even though the recipe only called for one or the other. The go big or go home theory did not work here as the sandwich turned really potatoey in the middle and wouldn’t hold its form, a total disgusting failure. The next time I tried it I kept both purees still and added more shredded cheese to the mix; this didn’t work either the oil that cam shooting out of this heart attack sandwich totally defeated the purpose of healthy eating and Jack was not impressed one bit. The third time was the charm and I followed the recipe down to the last teaspoon of olive oil, finally a winner. Jack devoured the sandwich with a side of beef vegetable soup which he took three bites of pushed away, I enjoyed the soup while Jack enjoyed the sandwich with no idea he was in fact eating more squash. The hubby stayed not impressed with this meal and I am beginning to hear shouts of how mean it is to trick the little guy.

Adventure Three: Spaghetti Pie with Broccoli and Carrots

This dish was right up my alley with it calling for two purees right off the bat. The more vegetables the merrier. This was a pasta layered dish that had meatballs made of hamburger and broccoli puree. The carrot puree was mixed with the noodles and cheese and then you baked the entire thing. I doubled the recipe for purees in this recipe as well. The broccoli turned the meatballs green and my husband was over it, he wasn’t even going to try the dish and ordered pizza. Jack had super fun making the meatballs, though I had to watch him like a hawk to make sure he wasn’t eating raw hamburger, which he tried and succeed in doing on several occasions. This final product was so good, though it was defiantly a weekend recipe, it took a long time to make and both Jack and I were starving by the time we finally sat down to eat. Another successful meal filled with hidden vegetables.

Adventure Four: Italian Meatloaf with Carrots, Celery, and Onions

The big winner to date! Jack stuffs this stuff down his throat at such a fierce rate I have to monitor how much is on his plate at one time so he doesn’t choke. Even my husband is on board with this dinner. I doubled the recipe the second time around and froze the extra for quick meals later on in the week. I decided to add mashed potatoes with cauliflower puree as a side and neither boy can tell it is not real potatoes.

Jack, Jessica, and I have cooked 23 of the 120 recipes in her book. Most have been hits, some are trial and error and some are terrible, stay away from the cauliflower Mac and cheese, it is just wrong to do that to good old fashioned Mac & cheese. My biggest critic is my husband who wonders if our child will ever know what good taste like, I try to convince him this is good food, he respectfully declines.

Our Garden, Mom and Me!

Our Garden, Mom and Me!

Every spring my mom and I plant a garden

We start in the dirt and dig with a hoe,

We get the ground ready by clearing the weeds

Preparing the soil so the vegetables will grow.

All the veggies have their own certain spot

The corn in the back, the lettuce up front.

The middle was filled with all kinds of yummy stuff,

Cucumbers, potatoes, peppers, and tomatoes.

Now working a garden is a real trying job,

You work and work in the hot afternoon sun

There are weeds to pull and plants to water

But it is all worth it for a fresh side of corn dipped in butter.

We eat from our garden all summer long

Fruit and veggies from the garden we have grown

Mom never waste a single precious plant

We make jellies, jams, and preserve whatever we can.

800 Pickers Wanted!

In the movie and book The Grapes of Wrath, the Joad family holds tight to the only thing they have left in life, the promise of work on flyer. This flyer and many produced like it is what sent so many displaced families to California. The following is what I see when I think of these flyers.

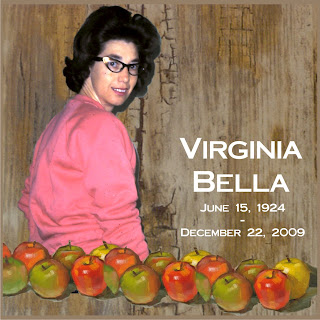

A tribute to my Grandma

When my Grandma died in December 2009 I was asked to speak at her funeral, I declined, I can’t speak in public even in happy times, my face gets red and I begin to mumble and speak fast, I avoid it at all cost. However I wanted to be a contributor to remember one of the strongest women I have ever known, so I did what I do best, I wrote, designed, and created her funeral program. At first glance this entry into a blog about farming and its role in hunger might seems strange, but not so much once you understand my Grandma Virginia and her story of survival of near starvation in the dust bowls of the thirties.

My Grandma Virginia was born in Oklahoma in 1924; she was 4 when she first remembered the winds beginning to blow on her family’s farm. Her dad was a sharecropper who scraped by just enough of a crop every year to feed his family of five kids, my grandma being the baby of the group. When the land stopped producing and the banks came calling for their note her dad over taken with too much burden left the family to starve to death on their Oklahoma farm. She never laid eyes on her dad again, something hardened on her heart that day that would never go away. My great-grandmother Lucas wasn’t going to sit by and let her family die, she made a deal with her neighbors and soon after she and her young family where headed to California holding those same flyers that promised work for all.

If people thought times were tough for families, try being a single woman with five kids competing against men in the field. My grandma and her family lived through every struggle that the Joad family encountered in Steinbeck’s book The Grapes of Wrath. They made it to California only to find no work and high predigest. They lived in transit camps and sometimes went days with nothing to eat. One of her brothers would eventually die from malnutrition. After spending almost a year following the harvest up and back the state they settled in Salinas, California where the boys and my great grandma worked on cannery row for many years before settling in Santa Cruz. Where she met and married my Papa and continued to live the life of a farm wife as she became to matriarch of Bella Orchards, a huge apple ranch running out of Aptos, California.

Those hard years of starvation forever changed my grandma, the hard shell that formed around her heart when her dad left them to die never softened. She was fun and easy to get along with but these was always a wall to prevent someone from getting too close, even her own children and grandchildren.

The following was my last tribute to the woman who taught me to what it means to take care of your family. That you can fight against any thing the world had to throw at you as long as you fought it with family.

NOTE: I did not write the poem on page two, I got it from a website dedicated to poems to use for funerals.

Monday, May 2, 2011

Interview with David Proctor of the Idaho Foodbank

I interviewed David Proctor with the Idaho Foodbank while he gave me a tour of the Boise facilities. It was a truly eye opening experience.

Christina Todd: How does the Idaho Foodbank work?

David Proctor: The Idaho Foodbank is a distributor of food. Our job is to collect all the food we can and distribute to local food pantries around the state.

CT: How many food pantries are there in Idaho?

DP: Over two hundred. We service them through this branch, one in Lewiston and one in Pocatello. There are only about 200 Foodbank like us around the whole country. A lot of food pantries like to use the word Foodbank in their name, but this is a rare distributorship.

CT: Do you receive government assistance?

DP: No we are complete privately funded, we rely heavily on private donations of money and food, the 20 to 30 small food drives going on around the area every week, and with our Grocery Alliance Program that picks up food from large grocery chains like Fred Meyer and Wal-Mart.

CT: What does hunger look like in Boise?

DP: A lot are working families who can’t afford to pay for rent, or utilities, or the gas in their cars and afford to pay for food. Most of these people don’t’ qualify for food stamp assistants from the states cause the supposedly make too much money, most don’t. The programs we have in place are there to help anyone who needs help.

CT: Can you tell me a little about some of your programs?

DP: The Mobile Food pantry is one of you biggest programs. There are a lot of rural towns in this state, some that don’t even have grocery stores and if they do the cost is so high they can’t afford to pay for it nor do they have the facilities in place to store the food we give them. Last week we went to Wendell, Idaho where we held our monthly food drop. We drive to the local fire department or church in area and with the help of volunteers we pass out food. In Wendell we park at the firehouse, when we pulled up to start unloading there was already a long line of people waiting to receive food, it didn’t just resemble a depression soup era soup line it was one. It is sad as the economy gets worse the lines are getting longer and longer, especially in the rural parts of the state.

CT: What is the backpack program all about?

DP: Oh this program is very dear to my heart. It was developed by a school teacher in the Midwest many years ago. Kids were going home o the weekends and starving, the relied on the free foods the schools gave them to eat. We fill a backpack every Friday for kids all across valley to prevent them from going hungry during the weekend. The sad face is right now we make 2000 of these. Every week we set up an assembly line on these tables where we stuff bags to be delivered to schools knowing that we could easily fill 7000 backpacks if we had the ability too.

CT: How much does it cost to produce a backpack meal?

DP: $6.11, it contains three square meals, none which have to be cooked, everything in this pack is child friendly, most kids who are going hungry on the weekends don’t have parents around.

CT: What do you think of forced volunteer work?

DP: I am on the fence about that. On one side we need all the help we can get, but having someone in here who doesn’t want to be can be very counterproductive, especially if that person is a teenager.

CT: Do you get a lot of fresh fruits and vegetables from the community when they begin harvesting their gardens?

DP: Yes we get a lot, but a lot of times people don’t know what to do with the vegetables. We will hand them a bag of mixed vegetables and they look at us like we are crazy. More often than not people will ask what the hell are we supposed to do with these. It has become such a problem that we now hand out recipe flyers with all the vegetables.

CT: So is it not smart to bring the Foodbank your surplus?

DP: No not at all, we never turn down any food. We have taken a big hit this last year in our food supply from the big chain stores, like Wal-Mart, who have opted to sell their damaged and mislabeled goods to the dollar stores instead of donating it to us and taking the tax write off. We need all the help we can get. I just wish more people knew what to do with a bag of vegetables I am worried more goes to waste then anything.

CT: Hungry people will throw away food?

DP: This is big problem. Every year we know a lot of pounds of food is wasted because people don’t know how to prepare it. Zucchini is the worst just because so many people grow it.

CT: So would that in mind would you think it would be beneficial for kids in school to learn how to cook vegetables?

DP: Yes, I believe if they had skills to cook them we wouldn’t be getting these stares that say are you kidding me we want real food.

CT: Are you afraid that people are become too dependent on your services?

DP: No, most people don’t like to come to food pantries to take hand outs. If there is a problem with someone working the system for free groceries it is very rare. We aren’t going to investigate; we go by the honor code that tells us if they are here they need help.

Interview with Stephanie Bella

This interview was conducted on February 26, 2011 in the kitchen of Stephanie Bella’s home over a perfectly brewed pot of coffee. Full disclosure on this interview, she is my younger sister, for the purpose of the interview I asked her to pretend we were not related and that I did not know her back story. I choose to interview her because we were both taught as kids the same valuable lessons of farming, gardening and preserving a harvest and knew this would be valuable information for my research topic.

Christina Todd: Tell me how the garden started.

Stephanie Bella: We are poor, we both work two jobs and can never seem to get ahead, and we had cut our budget time and time again and still couldn’t find the money to pay for everything. I was having a really bad day after making another call to another utility company begging for more time to pay the bills. I was crying at our patio door when it dawned on me, I own land, I know how to work land, I know how to grow things and preserve things, I am totally going grow stuff as much as I can to help with our grocery bill this summer.

CT: How did you know how to do these things?

SB: My grandma taught me. I grew up on an apple farm in California, farming is in my blood. My grandparent’s land produced so much food. There where berry bushes, plum trees, orange trees, lemon trees, a huge garden was planted every year, there was an herb garden and when I was about 12 they even installed a green house to continue to grow through the whole year. I can jar with the best of them, make strawberry jams and syrups, all sorts of good stuff. It was weird when I was old enough to be in school and realized that most of my classmates didn’t do any of this stuff.

CT: How did you start?

SB: I have Scott (her husband) remove all the sod on the left hand side of the house and just started growing stuff, before I knew it I had kind of an obsession going. After the first year we put in the berry bushes and the fruit trees and I packed every space I could with a food producing plant.

CT: How much does this really help you, is it really worth the time and energy?

SB: For sure. Don’t get me wrong, we still struggle, especially in early spring when the harvest runs out and the new one has yet to be produced, buy my grocery bill certainly feels relief at harvest time. We even compost our own stuff now, I feel good about that, it makes me feel very environmentally savvy.

CT: Tell me about your homemade baby food.

SB: I make my own baby food with fruit and veggies from my garden and a food processor, I pureed tons of vegetables and fruit from our garden last year and froze them, and that is what Charlie has been eating since he started on solid foods.

Letters of Inquiry

Please for give the picture of the email print outs, I could not for the life of me figure out how to publish a pdf file to my blog.

Film Analysis: The Grapes of Wrath

Christina Todd

Eng034w

Film Analysis

March 20, 2011

The Grapes of Wrath

Between the years of 1935 and 1940 thousands of farmers and their families were forced off their farms in Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, and Missouri onto Route 66 in search of the land of milk and honey: California. They followed the road searching for the promise of jobs, higher wage and a better life after banks began forcing them off their land that they had lived and worked for the last fifty years or more. Families ripped from their roots, with no place to call home, Okies as they became dubbed, found themselves on the long stretch of highway with empty stomachs and empty pockets (OKSTATE). In 1939 the world was introduced to the Joad family through John Steinbach’s Pulitzer Prize winning book, The Grapes of Wrath. The Joad family came to represent the hundreds of thousands of people thrown off their land and forced to chase a better way of life in California, a “simple and uncomplicated” (BEACH) story. In his essay, The Grapes of Wrath: A Novel of Mankind, Akira Nakachi discusses the two stories being told “on one side a tragic story of the migrant laborers driven on by antagonistic forces of nature and the social system till death stares then in the face, and on the other it is a forceful story of the migrants going forward over a number of obstacles” (NAKACHI}. The book evokes sympathy and anger in its audience as you read about the Joad’s sole quest to find honest work in order not to starve, you feel compassion for them and for every other family who had to do through this American tragedy, could a 128 minute film based on the book bring those same feeling to its audience?

In 1940 John Ford held the dubious task of bringing John Steinbeck’s heart wrenching epic tale of the Joad family to life on the big movie screen. The Grapes of Wrath stared Henry Fonda as Tom Joad who is the strength of the Joad family. “He is a man of action. He does what he thinks is right and never regrets what he has done” (NAKACHI). He is smart, but quick to anger, he sees the situation for what it is, he is not a dreamer, and the entire Joad clan relies on his knowledge to get them through. Jane Darwell won the 1941 Academy Award for best supporting actress for her portal of Ma Joad the family matriarch and the glue that tried desperately tried to keep the family together. The character of Ma Joad is a tribute to all the strong women who kept their families together through death, hunger, and circumstances beyond their control.

A freshly paroled Tom Joad returns home after a serving four years in prison for homicide. He discovers his family farm, along with those of all their neighbors, have been reposed by the banks. He arrives just in time as his entire family is set to leave for California the very next morning. In their old run down jalopy packed to the sky with family and belongings they travel Route 66 on their way to California with a flyer tucked in their pocket promising jobs and good wages. The movie tracks their travels to California as they encounter death and hunger, the camps and places along the way, the disappointment of the land of promise as they find themselves in transit camps and exploited for little pay by wealthy ranch owners, and the contempt and prejudice of native California’s who don’t want them there. Tom watches as his family falls apart and vows to take up the cause of his people. The movie closes with what is left of the Joad family back on the road following yet another promise of work (ERICKSON).

A series of three flashbacks narrated by a Muley Graves (John Qualen), a local crazy man so connected to his land that even after his family has left he stays prowling the deserted farms like a ghost, to tell the story of the evictions taking place across the state. In an eerie candlelight scene, which for seconds at a time go black, Tom and Jim Casey (John Carradine) coroner Muley demanding to know what is going on. The sound of wiping wind is heard in the background as Muley tells of dusters, notices, bankers, and caterpillar tractors. As Muley talks the screen shows several caterpillar tractors driving over dust blown farms and the sound of loud creaking tractors engulfs the audience eardrums, it resembles a march of destruction.

Ford uses filming effects like candlelight lighting, a moving score, a powerful panning shot, cryptic sound effects, and wonderful dialogue given by Ma Joad to tug at the heart strings of the viewing audience as the Joad’s say goodbye to the only life they have ever known. It is early in the morning, the sun has yet to rise and Ma Joad is sitting in the run down farm house all alone, the only light is coming from the old stove fire she is sitting in front of, this fire illuminates her face and little more. A sad accordion version of Red River Valley begins to play as she opens a small box next to her and begins going through its contents. The song moans on as she picks each item from her past up and holds it in the light, a small smile comes across her hard face as she looks at mementos from her past, one of the only times she will smile through the whole movie. The final scenes at the old farm seem to be pulled from old photographs; it is a head on shot of the running jalopy packed with the whole Joad family. Their rundown sad farmhouse is in the background, the truck pulls out of the frame, the viewer is left looking at the front of the house. The screens are ripped, the door is open, and there is trash everywhere. This still frame leaves little doubt to how poor this family really is. Suddenly you begin to hear the wind start blowing, softly at first, but then it begins to roar, you see it on the screen as a dust ball bounces through followed by a piece of news paper. The ratty old door begins to bang back and forth, bang, bang, bang. The camera pans to the left, we see the old jalopy headed down the dusty road, the accordion score of Red River Valley starts up again, the audience can still hear the wind and the banning of the door: bang, bang bang. Cut to a three-shot of the truck’s cab. Al, Grandma, and Ma Joad are driving away. Ma Joad is sitting tall with a hard stoic look on her face, she is staring straight ahead, and a stirring dialogue takes place between her and Al over the sad droning of the accordion:

AL :( grinning) Ain’t you gonna look back, Ma?--give the ol' place a last look?

MA JOAD :( coldly shaking her head) We're goin' to California, ain't we?

Awright then, let's *go* to California.

AL: (sobering) That don't sound like you, Ma. You never was like that before.

MA JOAD: I never had my house pushed over before. I never had my fambly stuck out on the road. I never had to lose... ever'thing I had in life (FORD).

Through his direction and great acting Ford is able to make his viewers feel the pain of saying goodbye, equal to that of the book. As a viewer you are connected with this family’s struggles and when it dawns in you that this family represents thousands you feel anger, but like the characters of the movie you too wonder who to direct this anger to.

A montage is used to show the rattling jalopies travel toward California. A US Highway 66 appears on the screen. Superimposed behind it is a montage ofThe Joad’s weighed down jalopy moving through farm land and cities. The signs of towns on U.S. Highway 66 fade in and out—Sallisaw City Limit, Checotah, Oklahoma City, Bethan, Peso River, New Mexico. Ford breaks up the montage to pull a couple . . . In the second half of the film John Ford spends the time introducing the audience to three very different migrant camps in California. He is showing us that upon arrival the Okies had three choices despair and hunger, tyranny rule, or if lucky enough to find a free space a government run camp. The first is the Hooverville Transient Camp, two miles outside city limits, clearly these people are unwanted. Using subjective view, Ford has the audience staring out the windshield from behind the wheel of the Joad’s old jalopy as it rattles its way through the crowded camp. Hungry and emaciated faces stare back at the viewer as the jalopy weaves through dirty tents and huts. The faces staring at you move slow, sometimes crossing the path of the jalopy, all faces are staring, none are happy, it looks like a city dump full of people. The feeling viewers get is that they have just rode through utter hopelessness, filth, and disillusionment. Through the subjective view you see the peoples hunger and despair. The second camp visited is the Kenne Fruit Ranch. This camp is representative of all the evil rich ranchers who exploited the tens of thousands of homeless and hungry Americans who were willing to do anything just for food. The scene is set so viewers know something wrong here; the camp gated and guarded by armed men, cops and yelling Okies line the road leading to the main gate. Again Ford uses subjective view to put the viewer in the driver’s seat of the jalopy as it is police escorted through the line of migrants and armed guards lining the side of the road. Like the Joad’s the viewers don’t know what the commotion is about, but something about this scene seems really wrong. Still using subjective view through the dirty windshield you see a migrant worker break free from the line, he is yelling, but like Tom Joad, we can’t hear what he is saying we only see him dragged back by more armed men. This camp is made to resemble later images of concentration camps, Ford focuses the camera on the hungry group who swarm the barbered wired gates after the Joad’s jalopy has passed through. The children’s little hands grasp through the chain link holes, they stare after the line of dusty cars, Ford focuses on the face of a young girl in a close up shot, the viewer’s like the Joad’s still don’t know what is going on, Ford makes it so you are herded along with the family to a dirty house, told to shut up and pick fruit and don’t ask questions. In almost every scene shot inside this camp a man can be seen holding a weapon, the men are short in tone and have a take it or leave it manner, by their expressions you know that they don’t’ care one bit about these starving families, if they won’t work for their low wages there is a line of starving people that will. An establishing shot of the sign welcomes the Joad’s to the Farmworker’s Wheat Patch Governement Camp. The camera closes in on the sign hanging underneath the camp name, it reads Department of Agriculture. This is the first camp that Ford does not use subjective view; he wants us to read the Joad’s faces as they finally find a place where they are welcomed. They are very weary of the camp’s director, who is dressed in bright colors, he has a smile on his face, and he resembles Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the man who would eventually help America out of the depression. In contrast to the other camps, everyone here looks healthy and many smiles can be seen on the Okie’s faces. Children run happy and healthy; viewers are left wondering why there aren’t more camps like this one?Sadly the massive scale of suffering in the book is absent in the movie. I had never seen the movie before this, but I had read the book several times over my life, as it tells part of my family’s history. When I chose the topic of hunger I knew there would be no better movie to watch then this one, based off my knowledge of the book, I was wrong. While Ford shows some struggles of the migrant worker, in the transit camps scene and in a story told by a man in a highway camp about his children who died with bellies swollen from hunger, he doesn’t delve into how bad the situation really was. Families piled on top of each other, floods and rains, abandoned barns filled to the rafters with families hungry and cold and dying. Ford’s adaptation of the film ends on an upbeat note, the family is headed towards twenty days of work and things are looking up, Ma Joad delivers the famous line, “That’s what makes us tough. Rich fellas come up an’ they die an’ their kids ain’t no good, an’ they die out. But we keep a-comin’. We’re the people that live. They can’t wipe us out. They can’t lick us. And we’ll go on forever, Pa . . . ‘cause . . . we’re the people” (FORD). Yet the end of the book tells a very different tale. The Joad’s are broken, on the verge of death and barely hanging on. They are headed to an abandoned barn in need of some shelter from the flooding, a man inside is dying of starvation, one of many heart wrenching scene of despair absent from the movie. In leaving these miserable conditions out of the movie, John Ford has done a disservice to the history of the Okies. Not only do we as viewers miss out on the intense suffering, but we also miss out on how amazing these people where, who fought dust bowls, tractors, prejudice, hunger, and death. For those wanting to know what is was really like for the Okies read the book, for those who want a happily ever after, stick to the movie, just remember a greater story of survival lies just beneath it’s surface.

Cited Works

BEACH: Joseph Warren Beach, “John Steinbeck: Art and Propaganda,” Steinbeck and His Critics. (Albuqueroue, 1956). P.252

DIRKS: Tim Dirks. “The Grapes of Wrath (1940)”. Filmsite. 2011. Web. 9 Mar. 2011.

ERICKSON: Glenn Erickson. “The Grapes of Wrath Review”. DVD Savant, 24 March. 2001. Web. 14 Feb. 2011.

FORD: Grapes of Wrath. Dir. John Ford. Perf. Henry Fonda, Jane Darwell, and John Carradine. Fox Home Entertainment., 1940. DVD.

NAKACHI: Akira Nakachi. “The Grapes of Wrath: A Novel of Mankind” Page 47-61. Print.

OWEN: Louis Ownes. “The Culpable Joads: Desentimentalizing the Grape of Wrath”. Critical Essays on Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, edited by John Disky, G.K. Hall. 1989. Print.

STEINBECK: Steinbeck, John. The Grapes of Wrath. New York: The Viking Press, Inc. 1939. Print.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)